Ever since the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF or Task Force) was created in 1984, the stature and weight of this volunteer group of 16 national experts in the fields of preventive medicine and primary care, including internal medicine, pediatrics, geriatrics, behavioral health, obstetrics/gynecology, and nursing, has grown significantly. So much so that the Affordable Care Act created a link between USPSTF recommendations and insurance coverage requirements. And since it’s linked to insurance, it is quite influential in defining the national health policies and public discourse.

So long story short, when the USPSTF publishes recommendations, the primary care professionals must pay attention!

The Task Force has issued many evidence-based recommendations about preventive services such as screenings, behavioral counseling, and preventive medications. These recommendations are created for primary care professionals by primary care professionals.

Today we will focus on 4 broad-based recommendations issued by the Task Force on anxiety, depression, and suicide risk for Adolescent, Pediatric, Adult and Senior population. Since the recommendations created for primary care professionals, it is pragmatic for all mental health therapists, social workers and counselors, to be aware of these. As these recommendations get implemented, they are bound to impact how you practice. If you are really short on time, jump to the last section on how therapists should comply with the USPSTF’s recommendations on depression and anxiety.

Unbundling USPSTF’s recommendations on Depression and Anxiety

| Recommendation Topic | Publishing Year | Age Group | Grade |

| Depression and Suicide Risk in Children and Adolescents: Screening | October 11, 2022 | Adolescent, Pediatric | B, I |

| Anxiety in Children and Adolescents: Screening | October 11, 2022 | Adolescent, Pediatric | B, I |

| Depression and Suicide Risk in Adults: Screening | June 20, 2023 | Adult, Senior | B, I |

| Anxiety Disorders in Adults: Screening | June 20, 2023 | Adult, Senior | B, I |

The first question that comes to mind when you look at the table is the last column about “Grade“. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force USPSTF assigns one of five letter grades (A, B, C, D, or I) when it issues any recommendations. Since the letters B and I are crucial to understand the recommendations, let me define the Grade B and Grade I here.

| Grade | Definition | Suggestions for Practice |

| B | The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial. | Offer or provide this service. |

| I | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. | Read the clinical considerations section of USPSTF Recommendation Statement. If the service is offered, patients should understand the uncertainty about the balance of benefits and harms. |

So as a therapist, one should offer the services recommended in Grade B recommendation without any disclaimers. And can also offer services recommended in Grade I with a disclaimer on efficacy.

The other grades are not relevant for this blog, but if you are curious about the other Grades, you can explore here.

Now let’s deep dive into each of the four recommendations one by one.

Depression and Suicide Risk in Children and Adolescents: Screening

Recommendation Summary

| Population | Recommendation | Grade |

| Adolescents aged 12 to 18 years | The USPSTF recommends screening for major depressive disorder (MDD) in adolescents aged 12 to 18 years. | B |

| Children 11 years or younger | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for MDD in children 11 years or younger. | I |

| Children and adolescents | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for suicide risk in children and adolescents. | I |

Clinician Summary and Practice Considerations

| To whom does this recommendation apply? | This recommendation applies to children and adolescents 18 years or younger who do not have a diagnosed depression disorder and who are not showing recognized signs or symptoms of depression. |

| Screening Tests | • Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) • PHQ modified for adolescents (PHQ-A) • Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-R) |

| Screening Intervals | • Repeated screening may be most productive in adolescents with risk factors for depression. • Opportunistic screening may be appropriate for adolescents, who may have infrequent health care visits. |

| How to implement this recommendation? | • Treatment options for MDD in children and adolescents include pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and collaborative care. • Clinicians should be aware of the risk factors, signs, and symptoms of depression and suicide, listen to any patient concerns, and make sure that persons who need help get it. Youth diagnosed with depression and their healthcare professional should decide together with the parents or guardians what treatment is right for them. |

| What additional information should clinicians know about this recommendation? | • All children aged 12 to 18 years are at risk of depression and should be screened. However, there are some factors that increase the risk. These include family history of depression, prior episodes of depression, childhood abuse or neglect, exposure to traumatic events or stress, bullying, maltreatment, adverse life events, and a difficult relationship with parents. Some gender identities and sexual orientations may increase risk of depression. • If antidepressants are used, the USPSTF recommends that healthcare professionals follow US Food and Drug Administration guidance and observe patients closely. • In the absence of evidence, healthcare professionals should use their judgement based on individual patient circumstances when determining whether to screen for MDD in children 7 years or younger or screen for suicide risk in youth not showing recognized signs or symptoms. |

| Where to read the full recommendation statement? | https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-depression-suicide-risk-children-adolescents |

Anxiety in Children and Adolescents: Screening

Recommendation Summary

| Population | Recommendation | Grade |

| Children and adolescents aged 8 to 18 years | The USPSTF recommends screening for anxiety in children and adolescents aged 8 to 18 years. | B |

| Children 7 years or younger | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for anxiety in children 7 years or younger. | I |

Clinician Summary and Practice Considerations

| To whom does this recommendation apply? | This recommendation applies to children and adolescents 18 years or younger who do not have a diagnosed anxiety disorder or are not showing recognized signs or symptoms of anxiety. |

| Screening Tests | • Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory for Children • Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) • Patient Health Questionnaire–Adolescent (GAD and panic disorder) |

| Screening Intervals | Repeated screening may be most productive in adolescents with risk factors for anxiety. Opportunistic screening may be appropriate for adolescents, who may have infrequent health care visits. |

| How to implement this recommendation? | • There are multiple treatment options available, including medications, counseling, a combination of these approaches, and collaborative care, which is a team approach where the primary care clinician works with a behavioral health care manager and psychiatrist to ensure patients receive the best care. • Clinicians should be aware of the risk factors, signs, and symptoms of anxiety, listen to any patient concerns, and make sure that persons who need help get it. Youth diagnosed with anxiety and their healthcare professional should decide together with the parents or guardians what treatment is right for them. |

| What additional information should clinicians know about this recommendation? | • Although all youth aged 8 to 18 years are at risk for anxiety and should be screened, there are factors that increase the risk. Risk factors for anxiety disorders include genetic, personality, and environmental factors, such as attachment difficulties, conflict between parents, parental overprotection, early parental separation, and child mistreatment. Certain groups are also at increased risk, including LGBTQ youth, transgender youth, and older adolescents aged 12 to 17 years. • In the absence of evidence, healthcare professionals should use their judgement based on individual patient circumstances when determining whether to screen for anxiety in youth 7 years or younger. |

| Where to read the full recommendation statement? | https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents |

Depression and Suicide Risk in Adults: Screening

Recommendation Summary

| Population | Recommendation | Grade |

| Adults, including pregnant and postpartum persons, and older adults (65 years or older) | The USPSTF recommends screening for depression in the adult population, including pregnant and postpartum persons, as well as older adults. | B |

| Adults, including pregnant and postpartum persons, and older adults (65 years or older) | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for suicide risk in the adult population, including pregnant and postpartum persons, as well as older adults. | I |

Clinician Summary and Practice Considerations

| To whom does this recommendation apply? | This recommendation applies to adults (19 years or older), pregnant and postpartum persons, and older adults (65 years or older) who do not have a diagnosed mental health disorder and are not showing recognized signs or symptoms of depression or suicide risk. |

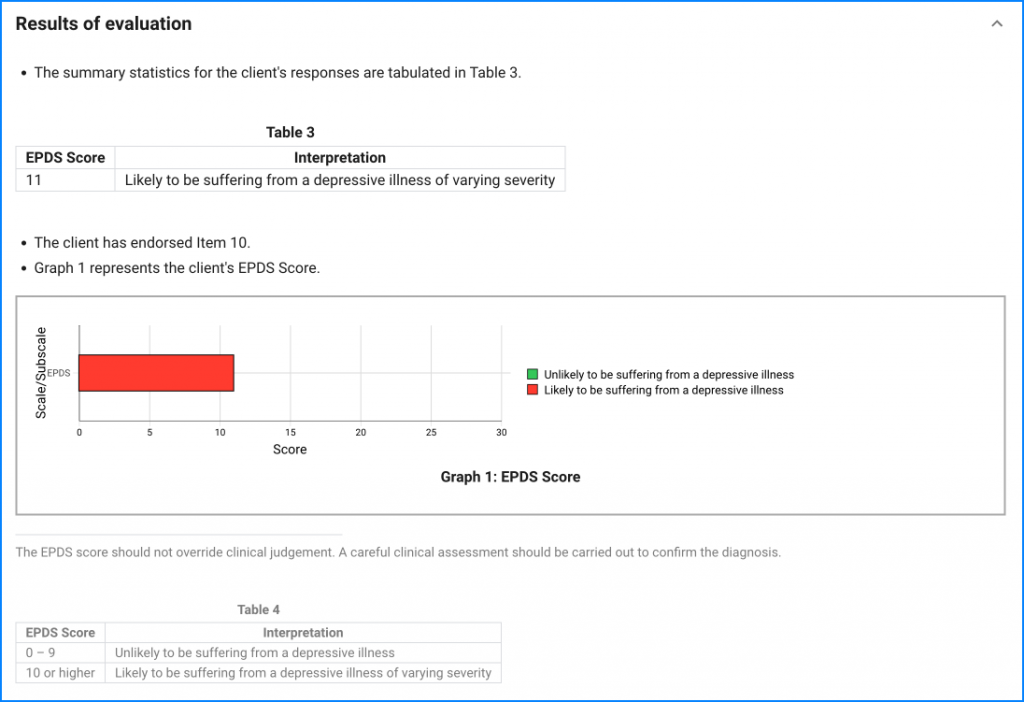

| Screening Tests | • Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) in various forms in adults • Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) • Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in older adults • Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in postpartum and pregnant persons • Beck Hopelessness Scale • SAD PERSONS Scale (Sex, Age, Depression, Previous attempt, • Ethanol abuse, Rational thinking loss, Social supports lacking, Organized plan, No spouse, Sickness) • SAFE-T (Suicide Assessment Five-step Evaluation and Triage) |

| Screening Intervals | • A pragmatic approach might include screening adults who have not been screened previously and using clinical judgment while considering risk factors, comorbid conditions, and life events to determine if additional screening of patients at increased risk is warranted. • Ongoing assessment of risks that may develop during pregnancy and the postpartum period is also a reasonable approach. |

| How to implement this recommendation? | • Treatment for MDD in adults includes psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy. Collaborative care is a multicomponent, health care system–level intervention that uses care managers to link primary care clinicians, patients, and mental health specialists to ensure patients receive the best care. Clinicians should be aware of the risk factors, signs, and symptoms of depression and suicide; listen to any patient concerns; and make sure that persons who need help get it. • To achieve the benefit of depression screening and reduce disparities in depression-associated morbidity, it is important that person who screen positive are evaluated further for diagnosis and, if appropriate, are provided or referred for evidence-based care. • Clinicians are encouraged to consider the unique balance of benefits and harms in the perinatal period when deciding the best treatment for depression for a pregnant or breastfeeding person. • The USPSTF found no evidence on the optimal frequency of screening for depression. In the absence of evidence, a pragmatic approach might include screening adults who have not been screened previously and using clinical judgment while considering risk factors, comorbid conditions, and life events to determine if additional screening of patients at increased risk is warranted. Ongoing assessment of risks that may develop during pregnancy and the postpartum period is also a reasonable approach. |

| What additional information should clinicians know about this recommendation? | • The USPSTF recommends screening for depression in all adults regardless of risk factors. However, there are some factors that increase risk. These include family history of depression, prior episodes of depression or other mental health conditions, a history of trauma or adverse life events, or a history of disease or illness. • Risk factors for perinatal depression include life stress, low social support, history of depression, marital or partner dissatisfaction, and a history of abuse. • Women, young adults, multiracial individuals, and Native American/Alaska Native individuals have higher rates of depression. • Anxiety and depressive disorders often overlap. • In the absence of evidence, health care professionals should use their judgement, based on individual patient circumstances, when determining whether to screen for suicide risk in adults not showing signs or symptoms. |

| Where to read the full recommendation statement? | https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-depression-suicide-risk-adults |

Anxiety Disorders in Adults: Screening

Recommendation Summary

| Population | Recommendation | Grade |

| Adults 64 years or younger, including pregnant and postpartum persons | The USPSTF recommends screening for anxiety disorders in adults, including pregnant and postpartum persons. | B |

| Older adults 65 years or older | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for anxiety disorders in older adults. | I |

Clinician Summary and Practice Considerations

| To whom does this recommendation apply? | This recommendation applies to adults (19 years or older), including pregnant and postpartum persons, and older adults (65 years or older) who do not have a diagnosed mental health disorder and are not showing recognized signs or symptoms of anxiety disorders. |

| Screening Tests | • Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) scale • Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) anxiety subscale • Geriatric Anxiety Scale (GAS) • Geriatric Anxiety Inventory (GAI) |

| Screening Intervals | • A pragmatic approach in the absence of evidence might include screening all adults who have not been screened previously and using clinical judgment in considering risk factors, comorbid conditions, and life events to determine if additional screening of high-risk patients is warranted. • Ongoing assessment of risks that may develop during pregnancy and the postpartum period is also a reasonable approach. |

| How to implement this recommendation? | • Treatment for anxiety disorders in adults can include psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy. Clinicians should be aware of the risk factors, signs, and symptoms of anxiety, listen to any patient concerns, and make sure that persons who need help get it. • To achieve the benefit of screening for anxiety disorders and reduce disparities in anxiety disorder–associated morbidity, it is important that persons who screen positive are evaluated further for diagnosis and, if appropriate, are provided or referred for evidence-based care. • Clinicians are encouraged to consider the unique balance of benefits and harms in the perinatal period when deciding the best treatment for anxiety disorders for a pregnant or breastfeeding person. • The USPSTF found no evidence on the optimal frequency of screening for anxiety disorders. In the absence of evidence, a pragmatic approach might include screening adults who have not been screened previously and using clinical judgment while considering risk factors, comorbid conditions, and life events to determine if additional screening of patients at increased risk is warranted. Ongoing assessment of risks that may develop during pregnancy and the postpartum period is also a reasonable approach. |

| What additional information should clinicians know about this recommendation? | • The USPSTF recommends screening for anxiety in adults 64 years or younger, including pregnant and postpartum persons, regardless of risk factors. However, there are some factors that increase risk. These include family history of mental health conditions, presence of other mental health conditions, a history of stressful life events, smoking or alcohol use, and marital status (widowed or divorced). • Women and Black individuals are also at risk. • Anxiety and depressive disorders often overlap. • In the absence of evidence, health care professionals should use their judgement based on individual patient circumstances when determining whether to screen for anxiety disorders in older adults 65 years or older. |

| Where to read the full recommendation statement? | https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/anxiety-adults-screening |

Checklist for Implementing the USPSTF’s Recommendations on Depression and Anxiety Screening

1. Incorporate Assessments and Repeated Measurements using tools like PsyPack

Incorporate Measurement-Based Care

Adopt standardized assessments as part of your routine to support both initial screenings and ongoing monitoring. The USPSTF recommends regular screenings to track treatment progress and adjust approaches as necessary.

Using PsyPack to Streamline Assessments in line with USPSTF’s recommendations

PsyPack can help you easily incorporate USPSTF’s recommended screening tools in your practice. PsyPack offers preloaded assessments tailored for various age groups and needs, including tools like the PHQ-9, GAD-7, CESD-R, GDS, and EPDS. These assessments, available for adolescents, adults, elders, and specialized groups like pregnant individuals, come with automatic report generation.

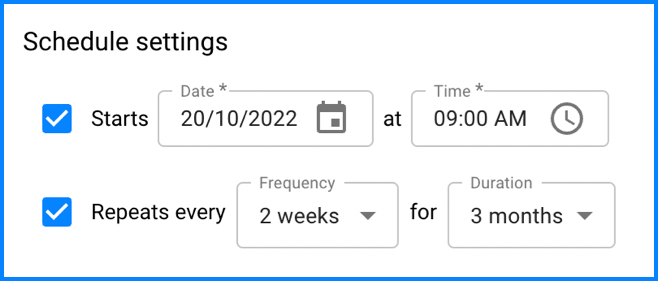

PsyPack’s Scheduling feature allows you to set recurring assessments at regular intervals, making it easy to track changes over time.

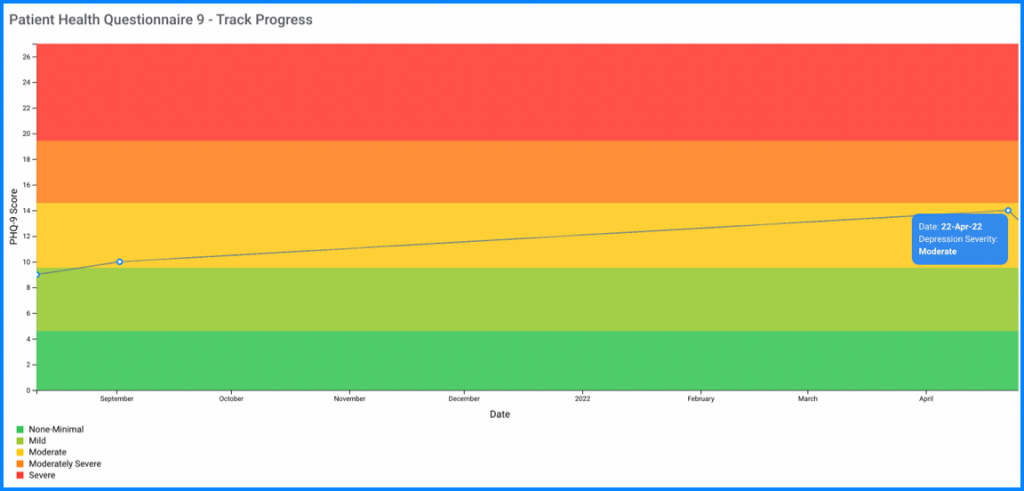

PsyPack’s progress tracking feature visualizes scores from various assessments on a single timeline graph, helping you assess treatment impact at a glance.

To get started, you can create a free account on PsyPack at psypack.com.

2. Identify and Consider Risk Factors in Intake Forms

Stay Educated on Risk Factors

Different age groups have distinct risk factors that can contribute to depression and anxiety. Understanding these factors—such as family history, trauma, social stressors, and comorbid conditions—enables you to recognize at-risk individuals early on.

Incorporate Risk Factors in Intake Forms

Adding questions related to risk factors in intake forms helps identify individuals who may benefit from closer monitoring and proactive support.

3. Foster Collaborative Care by involving Caregivers

Involve Parents or Guardians

For pediatric and adolescent clients, collaboration with parents or guardians is crucial. Work together to determine the best treatment plan, ensuring all parties are informed and engaged in the therapeutic process.

Encourage Open Communication

Encourage regular updates and open channels with family members to support children and adolescents effectively.

4. Involve GPs and Psychiatrists when medication is involved

Refer to Medical Experts When Necessary

If medications are required, ensure treatment aligns with the US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) guidelines. Build partnerships with general practitioners and psychiatrists to ensure a comprehensive approach to care.

Disclaimer: This blog reproduces recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). The content is provided for informational purposes and does not imply endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.